His electoral dominance PASOK in the national elections of October 18, 1981, caused nervousness and concern among Western governments, due to his pre-election announcements Andrea Papandreou to redefine, to a significant extent, the pro-Western orientation of Greece.

The first important samples of writing by the new PASOK government – at least at the level of declarations and directions – were given by Andreas Papandreou in an interview he gave to the American network ABC a few days after the elections and then in the program statements of the new government in Parliament in November 1981.

There, Papandreou made clear the PASOK government’s opposition to its existence in principle NATO and his Warsaw Pact and argued that the Atlantic alliance did not cover Greece’s defense needs. He also implied that Greece would withdraw from the military structures (i.e. the so-called “military branch“) of NATO, because the readmission agreement of (the Rogers deal of 1980), especially as it was applied, harmed Greek interests. However, it must be pointed out that even then he did not make any allusion to a possible complete withdrawal of Greece from NATO.

Furthermore, while he stated that the main concern of the government was “the formulation of an independent, genuinely multidimensional Greek foreign policy”, he clarified that the foreign policy of the PASOK government was also to be “a policy of realism”. On the issues of the country’s participation in the military structures of NATO and the removal of American bases from Greek territory, there would be careful moves and negotiations and not “unilateral actions”. At the same time, Papandreou emphasized that it was necessary to redefine Greek-American relations, but the goal of his government was to improve and deepen relations Greece – USA (on a more equal footing).

Exploratory meeting with the American Secretary of Defense

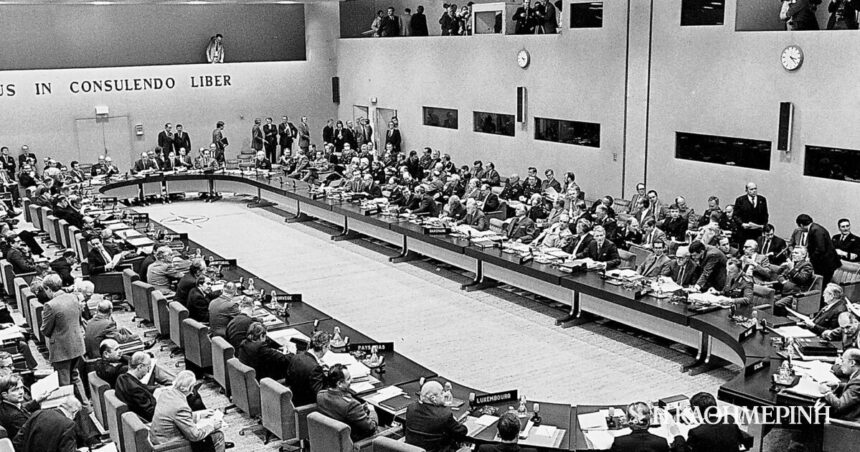

The first significant sample of writing about the relations between Greece under the government of PASOK and the Atlantic alliance was given in December 1981, when a meeting of the NATO defense ministers took place. Papandreou participated in the meeting, which took place on December 8, in his capacity as Minister of Defense of the country. Due to the well-known positions of PASOK and Papandreou’s previous announcements, the attitude of the new Greek government was awaited with great interest, which would be the first substantial example of its writing in an international forum.

Meanwhile, on December 7, the day before the controversial meeting, an informal meeting between Papandreou and the US Secretary of Defense took place Caspar Weinberger. This was Papandreou’s first – primarily exploratory – meeting after the elections with a high-ranking American official. Views were exchanged mainly on Greek-American relations and the main outstanding bilateral issues, but Papandreou developed the positions of the Greek government against the Turkish challenges and presented Greece’s defense problem. He assured that the PASOK government will not take hasty and unilateral actions on the issue of the operation of American bases in Greece. Referred to Cypriot and the need for the withdrawal of all foreign troops as a cornerstone for solving the problem, as well as the Turkish pressures, threats and arbitrary claims in the Aegean. He highlighted the Greek government’s concern about the possibility of overturning the military balance in the Aegean if the Washington abolished the ratio of 7 to 10 in the granting of military aid to Greece and Turkey: the maintenance of the military balance between Greece and Turkey was a means of guaranteeing Greek security, but it also contributed to the maintenance of peace and stability in the region. He also referred to the fact that NATO does not provide any cover to Greece against Turkish revisionism and requested that the alliance also provide a guarantee for Greece’s eastern borders. For his part, the US Secretary of Defense avoided directly addressing most of the above issues. In any case, the Papandreou-Weinberger conversation took place in a good atmosphere.

Athens has clearly, officially, raised the Greek security problem

The next day, during the meeting, Papandreou clearly explained the peculiar situation facing Greece within the Alliance and especially the security deficit, as well as the outstanding issues concerning the command and control regime in the eastern Aegean. He pointed out that Turkey, using weapons systems granted for (supposedly) defensive purposes within the framework of NATO, invaded in 1974 the Cyprus owning ever since illegally almost 40% of the island. In this action the Alliance he showed and continued to show indifference, which caused indignation among the Greek people.

Papandreou also stated that since then Turkey was threatening Greece itself and acting to revise the status quo in the Aegean Sea. A vehicle for serving these Turkish aspirations had become the ambiguity of the Rogers Agreement on the exact regime of command and control of NATO air operations in the eastern Aegean, where the Turks had not accepted the restoration of the pre-1974 regime, when the area was expressly under in the operational jurisdiction of Greece. He even warned that the Greek people, with their latest electoral verdict, authorized the Greek government to take whatever actions were necessary in order to free the country from agreements that are harmful to its interests. The above statements of Papandreou caused, as was reasonable, the fierce reaction of the Turkish Minister of Defense and great embarrassment to the ministers of the other states.

Afterwards, Papandreou directly requested that NATO proceed with the explicit guarantee of the security and territorial integrity of its member states (and thus of Greece), not only from external threats, but from wherever they came from. This proposal was rejected, despite conciliatory efforts attempted by other member states, as Turkey refused to be included in the announced paragraph with similar content. Then Papandreou made an important move in terms of symbolism, blocking by using the right of veto the issuance of a joint communique of the NATO member states.

The above action was then enthusiastically received by most of the Greek public opinion, while almost the entire Greek press positively assessed the Greek’s attitude prime minister. And this because it was considered by many to be a milestone in the struggle to protect national interests from 1975 onwards: Greece for the first time since August 1974, when it had temporarily withdrawn from the military arm of NATO, formally denounced the NATO partners that they showed tolerance towards the Turkish aggressive policy in Greece and Cyprus, in violation of the principles that supposedly governed the Atlantic Alliance. Athens clearly, officially and unequivocally raised the Greek security problem before NATO, even reaching the point of vetoing the issuance of the joint communique, in order to send a clear message.

New dynamics, but with moderation, in relations with the US and the Atlantic Alliance

In this phase, the allied governments – except for Turkey – reacted rather coolly. It was widely believed that the Greek government’s initiative to block the issuance of a joint communique was indicative of its intention, on the one hand, to satisfy the Greek public opinion, which expected a more non-committal and “proud” foreign policy, and on the other hand, to demonstrate in practice that Athens really considered Ankara – and not the Eastern bloc – as the primary threat.

Western officials did not consider the Greek stance a prelude to Greece’s withdrawal from the Alliance’s military structure. He wondered more “how much the Greek prime minister will keep the moderate line he is now following, in view of the pressure he is obviously under from the left wing of PASOK”. After all, the positions expressed by Papandreou did not come as a bolt from the blue.

Indeed, in general the new prime minister has been quite cautious during the first period after assuming power. Both his official statements or interviews and his actions indicated that he had to “keep in mind that the US was a superpower that had its own vital interests in the region” and that he had no intention of leading Greece into confrontation with the USA or withdrawing from NATO. Besides, at the same time, Andreas Papandreou made it clear that his government could not veto issues which, while they were of critical importance for the operation and strategy of the Alliance, did not directly affect vital Greek interests (as they were, for for example, the accession of Spain to NATO).

In January 1982, the Greek prime minister met with the American ambassador in Athens, Monteagle Stearns, and made it clear that Greece wished to remain in the Western camp: “the form of Greece’s cooperation with NATO would be subject to negotiation, but not the fact ( of cooperation) as such”. The Americans showed similar moderation.

Of course, the above did not mean that Greek-American relations were clear or that Greece was considered a “normal” NATO ally. But the fact is that Greek-American relations deteriorated much later, after the summer of 1983. And in fact, after an agreement was first reached between the two governments on the continuation of the operation of the American bases in Greece.

*Mr. Dionysis Hourhoulis is an assistant professor at the Department of History of the Ionian University.