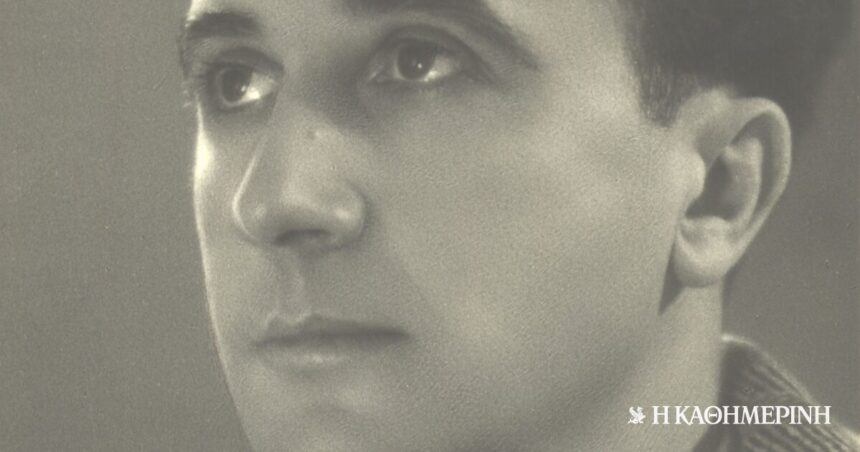

The director Dimitris Rontiris (Poros, 7/1/1899 – Athens, 20/12/1981) appears in the theatrical events of interwar Athens in a period of multifaceted development, but also of serious crisis. The institution of the director is at the vanguard of artistic renewal, while the establishment of the National Theater decisively changes the balance of the theatrical ecosystem. The new artist with integrity, professionalism and perfect technique will determine developments: he will impose the model of the director-teacher and participate in the formation of the leading theater institution of the time. It will star in the so-called “revival” of ancient drama and its presentation in open theaters, forming a dominant interpretive model.

The youngest of the five children of the judge Achilleas Rodiris and Kostoulas (nee Levantis) deviates from the urban family traditions of military and legal studies to engage in theater. Since 1918, he has known important artists such as Emilios Veakis, Fotos Politis, Thomas Oikonomou and Marika Kotopoulis. For a decade he has been active as an actor, while occasionally collaborating with theatrical publications and translating. He made his directorial debut with the opera “Mother’s Ring”, by Manolis Kalomiris (1928). In 1930-1933 he studied abroad, initially with a scholarship of the Athens Academy and later as a scholarship, correspondent of the National Theatre. He gains experiences from different institutions and apprenticeships: he studies art history in Vienna, attends the Reinhard seminar, apprentices at the Burgtheater, attends tests and events of important theater organizations.

Historical performances at the National Theatre

In 1933, he was appointed to the National Theater and, after the death of Photos Politis, took over as first director. His performances set new standards of quality, with prominent performers and the support of important collaborators, such as Kleoboulos Clonis and Antonis Fokas. It is established with the five-hour performance of “Peer Gund” by Ibsen (1935). The play is being performed for the first time in Greece, just like Kleist’s “Prince of Homburg” (1938). Until his resignation (1942) he directed more than forty productions, such as “Triseugene” by Kostis Palamas (1935), the Shakespearean “Hamlet” (1937) and “King Lear” (1938) with Emilios Veakis, in a leading moment of his career.

The emblematic play of the Sophocles “Electra”, with Katina Paxinou and Eleni Papadakis, was staged at Herodeion (1936) and Epidaurus (1938), ushering in the use of Argolic theater in modern times. Along with “Hamlet”, they were presented in England and Germany (1939), bringing the director face to face with a non-speaking audience and giving him a triumph, at the same time confirming the use of the theater as a means of cultural diplomacy.

Takes over as director of the National Theater during the Civil War. If before the war the director’s name was associated with serious steps of progress, his first managerial term (1946-1950) is identified with a dark era of administrative authoritarianism and ideological-artistic entrenchment. The classical repertoire dominates, from which the first Greek presentation of Shakespeare’s “Richard II” (1947) stands out. The pre-war “Persians” of Aeschylus are repeated, which are also presented in Rhodes, a few months after the integration of the Dodecanese. The political dimensions of the recruitment can be seen in the press, just like in “Oresteia”, which was staged at the Herodeion in September 1949, shortly after the end of the Civil War. The Aeschylian trilogy was one of Dimitris Rodiris’ best performances up to that point, thanks to the many months of preparation of the Dance and the cooperation of Marika Kotopoulis. In 1952, “Electra” was included in the first tour of the National in the USA. The following year, Dimitris Rontiris returns as general manager of the organization. “Hippolytus” by Euripides in Epidaurus (1954) is repeated, with Alekos Alexandrakis, and many famous guests. The official opening of the festival, however, takes place next summer, while the director has already been fired from the organization. He will return to Epidaurus with the National twice more: in 1959 with “Oresteia” and in 1978 with “Elektra”, his last direction.

The Piraeus Theatre

The Piraeus Theater is the second attempt by Dimitris Rodiris to create his own troupe, after the short-lived Hellenic Stage (1950-1951). He tours throughout Europe, the Soviet Union, the United States and Latin America, exclusively with works of ancient drama. “Medea” (1962) and “Iphigenia en Avlidis” (1967) by Euripides are added to the already formed productions (“Electra”, “Perses”, “Hoiforoi” – “Eumenides”, “Hippolytus”). The constant collaborators of the troupe are Thodoros Kritas, in the organization, the choreographer Loukia, the musician Konstantinos Kydoniatis, the actors Aspasia Papathanasiou, Antonis Xenakis, Titika Nikiforakis, Nikos Hatziskos, Elsa Vergi, Kostas Galanakis, Christos Fragos, Miranda Zafeiropoulou and many others.

While the Greek theater scene is dynamically entering a new era, the director sticks to his already formed interpretive proposal. At the same time, it contributes to the extroversion of the Greek theater, highlighting the ancient drama as an exportable cultural product and gaining international recognition, with several honors and participation in important international festivals.

As a teacher he required ascetic discipline

Dimitris Rontiris made a decisive contribution to professional theatrical education by teaching dozens of actors, who subsequently followed his path. The accounts converge on the image of an authoritarian teacher-father, with strong likes and dislikes, who offered and demanded ascetic discipline in an initiation process. It focused on breathing, voice and articulation – the control, that is, of the means of expression that support the rendering of emotion, the channeling of emotion and the emergence of what for the teacher came first: poetic speech. Addressing the texts in musical terms, he sought to form “complete instruments”, notes Kostas Georgousopoulos, capable of rendering, under his strict direction, the complex score of the theatrical discourse.

He directed over 80 projects during his multi-year career. In general, his performances at the National Theater highlighted the institution’s prestige with spectacular stagings, organized ensembles and flawless use of the technical and stage possibilities. The size fit into a disciplined stage environment, suitable for large performances, where unerring diction, rhythm, prosody and ups and downs of intensity – precisely noted in the direction books – functioned as carriers of the discourse. Directing in the service of the text sought to render meanings and not to materialize a personal directed reading.

Dimitris Rontiris devoted himself to the creation of a universal performance code for what he considered to be the correct interpretation of ancient drama, applicable to all works and regardless of the historical context of the performances. This idealistic approach was based on the promotion of universal values, on the ritualistic dimension of ancient drama and on the special lyrical essence of the Dance, which he tried to lead from rhythmic recitation to a special type of hymn. He sought the tragic chill and the aesthetic thrill in emotion and dramatic conflicts, but through strict forms of rhythm and movement. His scenic images drew on the beauty of classical sculpture and his physicality was characterized by discipline and decorum. In his own version of Greekness, at about the same time that Karolos Koon was researching “popular expressionism”, he attempted a combination of distinctive elements of the Byzantine and municipal tradition with the scholarly and the monumental.

About a century separates us from the time when Dimitris Rontiris appeared dynamically in the regional theater scene of interwar Greece. His personality was characterized by tensions: strictness, which was considered paternal affection, but also authoritarianism; unwavering convictions, which for some meant the promotion of the classics, integrity and patriotism, while for others entrenched in ideological and artistic conservatism. His manner – because of its uncritical mimicry, his admirers insisted – became synonymous with a mechanistic bigotry that limited the artistic imagination; however, it was decisive for important artists. And if for years he was, positively or negatively, behind every attempt to present ancient drama, today could modern theater art be fermented with his work and personality? The thought of a younger important director, Lefteris Vogiatzis, is perhaps useful here: “This form creates for me a feeling of trust and a deeper agreement… with something”.

Mrs. Evdokia Delipetrou is a theater expert, doctor of the Department of Theater Studies of the Greek Academy of Sciences.