November 18, 1940

A rather enigmatic Ribbentrop meets me in Salzburg. Before the meal, at his home in Fusl, he decides to speak, that is, to announce that Hitler will speak about the situation created by the Greek crisis. Germans are sullen and it’s not hard to see why. […]

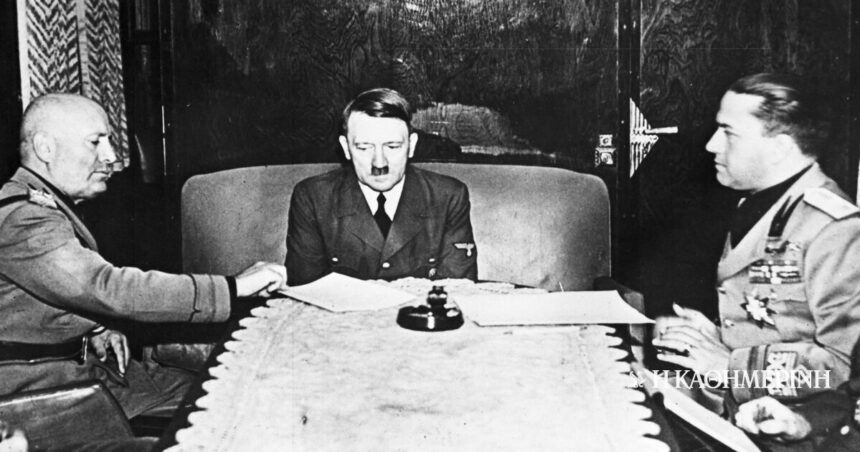

In the afternoon I saw Hitler at the Berghof. A long tea with Serrano [υπουργός Εξωτερικών της Ισπανίας] and the others, and then a personal discussion with Hitler, Ribbentrop and an interpreter. I described the discussion in a letter to Duce. There was a heavy atmosphere. Hitler is pessimistic and believes that the situation is greatly aggravated by what happened in the Balkans. His criticism is open, specific and definitive. I try to talk to him, but he won’t let me go. Only in the second part of the conversation, after Hitler has given his consent to possible negotiations with Yugoslavia, does he become warm and cordial, sometimes almost friendly. The idea of an alliance with Yugoslavia excites himto the point that while his pessimism at first looked very black now his optimism looks very rosy.

November 19, 1940 [συνέχεια της 18ης Νοεμβρίου]

He tells me some secrets: even that Horty urged him during his trip to Italy to raise the question of Trieste, that is, that he wanted to launch Hungarian nationalist claims in Fiume. (Can I believe all this?) “For now,” Hitler added, “it is necessary to pretend to the Hungarians, as we need their railways. But the time will come when we will speak clearly.” (However he hides, the Hungarians know his ideas very well). From the hotel I write a long letter to the Duce. I emphasize the Yugoslav case, because I am convinced that it will be very popular with the Germans at this time. I believe Mussolini will strongly object, at least refuse any military assistance in this matter before taking his revenge on the Greeks.

Alternative news about defeats and victories on the Albanian front. I’m afraid we’ll have to retreat to a predetermined line. The loss of Korça is certainly not the loss of Paris, but it will serve to give a name to the battle and help the enemy beat the drums of propaganda against Italy. That’s why I hope we can keep Korca.

I go to Vienna by train.

With these brief entries in his personal diary the Italian foreign minister and Mussolini’s son-in-law records, Galeaccio Cianowhat happened during his meeting with Adolf Hitler himself at the latter’s imposing residence in Obersalzberg on November 18, 1940.

Italy’s apparently ill-conceived invasion of Greece, which had begun almost a month earlier, had become a serious strategic headache for the Axis. Driven by Mussolini’s ambitions to extend Italian influence in the Balkans, Italy launched its invasion of Greece on October 28, 1940, without consulting Germany. While Mussolini sought to build an empire to rival Hitler’s recent successes, the invasion instead turned into a quagmire. The Italian army, hampered by supply and logistics problems, the rough terrain of the Greek-Albanian border, and unexpectedly strong Greek resistance, was soon forced into a defensive position. By mid-November, his situation in Greece was dire, with troops retreating and morale faltering. Mussolini’s miscalculation not only damaged Italy’s credibility, but jeopardized broader Axis goals.

The Balkans were particularly critical for the Reich.

Germany saw the Italian campaign as disruptive, as Hitler hoped to hold the Balkans steady while he focused on Britain and prepared for an eventual invasion of the Soviet Union. The Balkans were particularly critical to the Reich because of Romania’s oil fields, which were essential to fuel the German war effort. Italy’s attack on Greece threatened this stability, giving Britain a potential foothold in the region. British forces, seeing an opportunity, quickly began supporting the Greek defenses with material aid and air support. This escalation raised fears that the British might establish air bases in Greece capable of reaching the oil wells at Ploesti in Romaniawhich Hitler could not afford to lose.

At their meeting, Hitler sharply criticized Ciano – and by extension Mussolini – pointing out that the Italian campaign was draining valuable resources from the North African front and straining Italian forces. Mussolini’s decision had forced Italy to redirect its already limited military resources, as five times as many Italian troops and much more equipment were sent to Albania and Greece than to North Africa. The Italian navy and air force, which could have been deployed in the Mediterranean to protect critical supply lines, were now limited. Italian military leaders, including Chief of the General Staff Hugo Cavallero, prioritized Greek operations over strengthening Italian positions in North Africa. This diversion left the Italian troops weakened there, where they faced increasing British pressure. Rodolfo Graziani, commander of Italian forces in North Africa, was left with few resources as Italian shipments and reinforcements were routed to Greece.

Hitler saw Italy as more useful as a distraction than as a critical military partner.

Hitler, who had long doubted Italy’s military capabilities, saw this failure as confirmation that Italy was, at best, a minor partner within the Axis. Germany’s initial alliance with Italy was never equal: Hitler saw her role more as a useful distraction for the Allied forces than as a critical military partner. The campaign against Greece revealed the lack of coordination within the Axis forces. German resources earmarked for the Eastern Front were now allocated to help stabilize the Italian front in Greece. By early 1941, the German High Command was planning an invasion of Greece to rescue Italian forces, a diversion that would ultimately delay Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, by several weeks. This delay would have a significant impact on the German campaign in Russia, as it exposed German forces to the harsh Russian winter, contributing to the subsequent setbacks that proved disastrous for the Axis.

The invasion of Greece not only burdened the Italian army, but also weakened Mussolini’s political position within his country. Discontent grew within the Fascist party and the Italian army, whose morale had been shaken by high casualties in Greece.. Italian officers faced severe criticism and Mussolini’s closest allies began to lose confidence in his leadership. By early 1941, both Italian resources and civilian morale and support were depleted.

The meeting of 18 November 1940 thus marked a turning point in the Axis alliance.

The meeting of 18 November 1940 thus marked a turning point in the Axis alliance. While Germany would eventually intervene in Greece, the Italian failure highlighted the differences of power and strategic vision within the Axis. From this point on, Germany would take a more dominant role in guiding Axis strategy and Italy would be increasingly marginalized. For Hitler, the Italian invasion of Greece was not just a military failure: it was a stark reminder of Italy’s limitations as an ally and the cost of Mussolini’s unchecked ambitions.

Column editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigoni-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis